The perfect match

How a new blood test is making it easier to find the best match for patients

Our scientists have developed a rapid and comprehensive test for determining all blood groups in donors. This new test builds on decades of genomics and blood group research and could transform how we characterise donors. Use of the test will make it much easier to find matched units for the most vulnerable patients.

Each year millions of blood transfusions provide life-saving support to patients. However, transfusions are not without complications. One patient in every 30 will develop antibodies against the minor blood group systems present in all blood.

Antibodies are produced in response to antigens that the body does not recognise. This can happen when a patient is exposed to non-self antigens from another person via a blood transfusion: the immune system does not recognise the foreign antigens and produces antibodies against them.

What is a blood group?

Blood groups are determined by the presence or absence of antigens (or markers) on human blood cells. Antigens are protein molecules found on the surface of red blood cells which can be recognised by antibodies, another type of protein molecule located in the blood plasma.

The different types and combinations of these molecules give us our blood type: A, B, AB or O – as well as RhD factor (+ or -).

For most of us, matching the ABO groups is generally straightforward. However, there are not just ABO antigens on the red cells – in fact, there are over 360 different antigens that we know of.

Once a patient has developed an antibody, they need blood that is negative for the corresponding antigen from that point on in order to avoid a transfusion reaction. This means that identifying compatible units for patients with antibodies becomes more complicated as future transfusions must be from donors who are more precisely matched. This is particularly the case for those who receive regular transfusions, such as people with sickle cell disease.

To provide precisely matched blood transfusions, we type one out of every six donors for far more blood group systems than the standard ABO and RhD.

Now researchers at the University of Cambridge have developed a simple DNA test for typing nearly all the clinically relevant red cell blood groups.

The blood transfusion genomics consortium extracted DNA from donor blood samples and produced a “genotype" for each individual by looking for specific genetic changes which are related to blood type.

The fully automated test also generates results for the Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA), and the Human Platelet Antigen (HPA) types. Knowing the HLA and HPA type allows rapid identification of valuable platelet and stem cell donors.

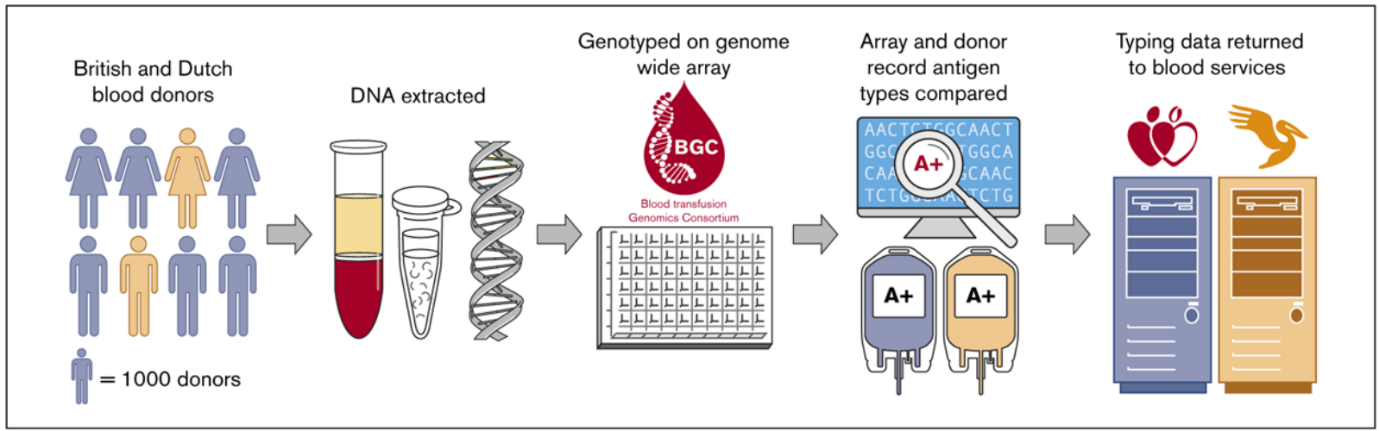

A diagram showing how the study was conducted:

First, DNA was extracted from 7,000 blood samples of British and Dutch donors. Second, the researchers typed the DNA of each participating donor and used the data to identify their blood groups. Third, the researchers compared the genetic blood typing data to the blood typing data that was already on donor record and observed that the new test was extremely accurate. Finally, the genetic blood typing data produced by the study was returned to the blood services of each country for use.

The good news is this test is very affordable, easy to use, and compares very favourably with the many tests currently used by the blood services in England and the Netherlands. The large number of typing results produced by the test makes it twice as likely that a compatible donor can be found for a particular patient.

The other good news is that the DNA sequence data being generated contains information that is highly relevant to the transfusion medicine community. It provides opportunities to optimise blood donor management and improve patient care, and greatly simplifies the challenges of providing blood.

The next stage in this exciting project is to bring this precision medicine test to the bedside of NHS patients and increase the number of donors tested. Planned recruitment of donors to the UK 5 Million Early Disease Detection Research Project will lead to a significant increase in the number of donors being typed with this new test.

If you would like to learn more, you can read the full publication.